Holocaust, 1984-1998

Grodnow, 1989, 18" x 23", mixed media on paper

Fear, Panic, and Surrender, 1987, 44" x 72", mixed media on paper

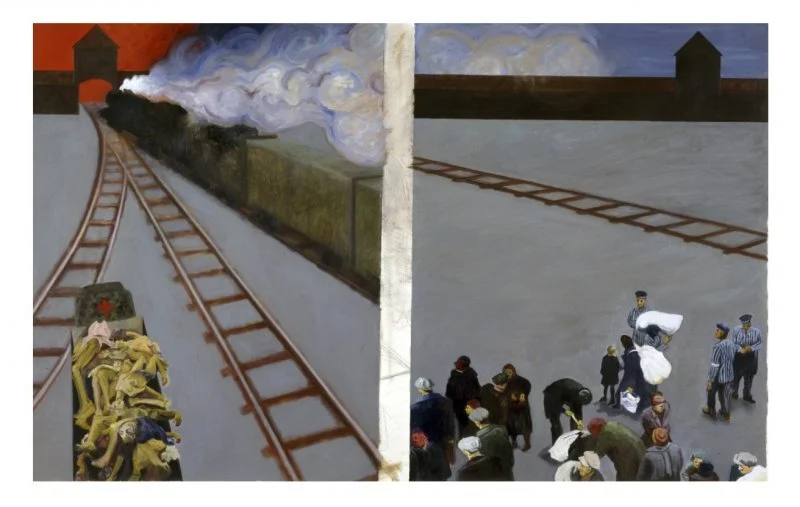

Arrival, 1987, 44" x 72", mixed media on paper

Destroying the Stones, 1987, 44" x 72", mixed media on paper

Hanging the Resistance Fighters, 1987, 44" x 72", mixed media on paper

The Butcher, 1987, 72" x 44", mixed media on paper

A Pale Horse, 1987, 44" x 72", mixed media on paper

Burial in the Ghetto, 1987, 72" x 44", graphite on paper

Aktion, 1987, 44" x 72", mixed media on paper

Self Portrait, 1997, 22" x 30", mixed media on paper

General Stroop Report, 1997, 22" x 30", mixed media on paper

3 Wild Dogs, 1997, 22" x 30", mixed media on paper

Resettlement, 1987, 72" x 44", mixed media on paper

Aktion, Poland, 1987, 44' x 72" , graphite on Paper

Prisoners at a Burning Village, 1997, 22" x 30", mixed media on paper

Starifixion, 1992, 56" x 40", road-kill, woodcut and oil on aluminum

2 Dogs at a Burning Synagogue, 1992, 56" x 39" , mixed media on aluminium

Dogs at the Wall, 1998, 22" x 30", mixed media on paper

Nuremberg, 1998, 22" x 30", mixed media on paper

Schowola, 1993, 62" x 45", oil, graphite and aluminium on canvas

Two Abandoned Horses, 1997, 36" x 50", oil on canvas

The Eagle and the Rabbit, 1998, 22" x 30", mixed media on paper

Memento Mori, 1997, 22" x 30", mixed media on paper

The Barracks, 1987, 44" x 144", graphite on paper

Self Portrait, Gabin, 1990, 51" x 35", oil on paper

Installation at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, NY

FIRE PAINTINGS AND THE BOOK OF FIRE

Although he was born to make the images in the present exhibition, Murray Zimiles waited until the flaming color of his hair was losing its luster before he began, six years ago to confront the Holocaust. The moral question of who may bear witness to the Holocaust, so forcefully raised by Elie Wiesel, obliged Zimiles, "the victim of a victim" to consult his conscience before exhibiting these works in a commercial gallery. An earlier set of 26 enormous paintings and drawings depicting the major events of the Nazi genocide, have never been seen outside his studio. Spare and direct in their power to make one weep, these paintings must be viewed where their impact may be experienced inwardly.

Zimiles has built or constructed four houses, two studios, and one dune shack in his life. He has co-authored a book on early American mills, and travelling in Europe, he has obsessively visited collections of folk architecture in Norway, Belgium, Sweden, and Holland. But it was not until he discovered a poorly printed book, published in Poland shortly after the war, that he learned of the existence and total destruction of numerous synagogues, masterfully constructed entirely of local timbers. These occupied the center of provincial communities. Each was at once a house of worship, a place of assembly, and a living repository of rich and scholarly tradition. One by one, in quick succession, the buildings were destroyed by fire. The Book of Fire bears witness to the Nazi atrocities committed against the Jews by citing eyewitness accounts gathered from people entering the Warsaw Ghetto, accounts buried in milk cans for safety and retrieved at the end of the war. Their voices breath fire.

Fire has always been revered for its power of transforming the negative into the positive, and has provided us with an alternative history of things rising out of ashes. The wooden Polish synagogues made excellent tinder for the Nazis torch. In one of his Fire Paintings, "Self Portrait," Zimiles shows how the shadows cast by leaping flames light up from below the moonfaced and vaguely oriental dome, which surmounts a burning synagogue. Fleeing the catastrophe, running directly at the viewer, is the artist's likeness, a bearded man with a naked athletic chest. He seems pressed into the very heat he flees, emerging from the painted fire like a ghost going through a solid wall.

For the past 20 years, in his paintings and drawings and prints, Zimiles has pursued a narrative form of visual art. He declares frankly that aesthetics, for him, is the secondary interest, and that he has rarely seen an abstract painting which went beyond being a decorative object. Usually he develops a series around a central theme, showing cinematic aspects of separate temporal moments. Often the same figure has two or three bodies, one of which may be precisely or even academically drawn, another blurred by the streak of an eraser or a wide brush, a third in silhouette. Sometimes the distortions of a face or figure will suggest the odd violence of Francis Bacon, but Zimiles" true precursor is Munch whose work he absorbed in 1970 in Oslo while on a grant from the Norwegian Government. From Munch, Zimiles learned that a moment of violence cannot be understood aesthetically.

The Book of Fire is a physical object that is as tall as a man and wider than his armspan. Theoretically, it is an accordion book, which means that all its pages can be shown at once if thy are stretched out on zig zag mounts along an 80-foot wall. Some of the Fire Paintings are very much like the prints in the book because they were actually painted on the very plates used to pull the prints. One is reminded that Zimiles has always worked in series, and that printmaking itself is a medium which concerns itself with multiples. Ordinarily an edition is cancelled by destroying the plate. Zimiles chose to let the lithographic ink dry on the plates before layering the image with a second, painted surface, creating a curious doubling which both links and elaborates the connections between the paintings and the pages of the book. Those plates have become paintings. They will never be used again to make a print. Though Zimiles admits this is "a crazy way of cancelling the plates" he has succeeded in redeeming what has been destroyed.

Christopher Busa

Editor of Provincetown Arts